Everyone Agrees Encampments Aren’t the Solution

When listening to candidates for city office, it’s often hard to tell what—if anything—will change in how Minneapolis addresses homelessness. Nearly everyone agrees that encampments are unsafe for both residents and neighborhoods. The harder question is: what comes next?

Most candidates say that more deeply affordable housing is needed. But where should it go? And how will it be paid for? Those details are rarely discussed.

That’s why the city needs leaders committed to working with county and state partners to solve the problem. It’s easy to issue press releases about individual “rights.” It’s much harder to do the math—and make the deals—that turn rights into real housing.

Audit Hennepin County

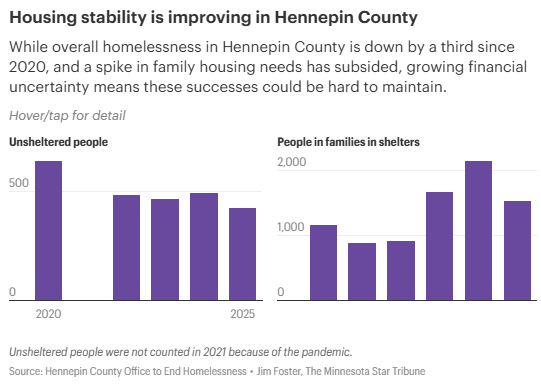

The Star Tribune recently reported that homelessness in Hennepin County has dropped 33% since pandemic highs. That is a notable accomplishment. However, when you examine the math, questions arise.

Hennepin County says it spends $190 million annually to keep homelessness “rare, brief, and nonrecurring.” In 2024, when 2,650 people were unsheltered, that translated to $71,698 per person. In 2025, with a reduced population of 1,965, the cost per person rises to $96,692.

This is only the county’s spending. It does not include city or state funds. Out of the county’s $2.68 billion annual budget, homelessness services consume about 7%. That raises a fair question: how many other county programs—from roads to health care—are producing fewer results than the money suggests they should?

Consider the housing market. According to Apartments.com, Minneapolis rents rose 2.8% last year, with the average one-bedroom at $1,391. More than 8,200 apartments are currently available. Covering rent for every unsheltered person for a year would cost roughly $33 million at market rates. Add another $40 million for job training and health care, and the total would be about $75 million—still far less than the $190 million the county currently spends.

An audit is needed to explain how the county is spending nearly $200 million annually on fewer than 2,000 people. Without transparency and results-based accountability, well-intentioned programs turn into waste. Budgets are already tightening, and federal Medicaid cuts will make that worse. These figures suggest the homelessness problem is less about funding and more about management.

Solving homelessness in Minneapolis is not just about Mayor Jacob Frey or the absence of safe outdoor spaces. It is about whether state, county, and city leaders can work together to stop the leakage in overlapping programs. Raising taxes by double digits while mismanaging budgets is not sustainable. Calls for social justice are welcome, but at this moment, we also need politicians who can do the math.

Interview Summary

Mark Andrew served as a Hennepin County Commissioner from 1983-1999 and was the Chair of the Minnesota DFL from 1995-1997. He spoke with me about his long career in public service and the city’s current challenges.

A Minneapolis native, Andrew recalled his years on the Hennepin County board, which funds many of our social programs, including those focused on homelessness, mental health, and youth services. He described the city’s role as handling “bricks and mortar” services like police and zoning, while the county is charged with human services.

On gun violence, Andrew expressed frustration with federal inaction and cuts to mental health funding. He called it “beyond hypocritical” for leaders to demand more treatment while stripping resources from programs that could prevent tragedies. He also argued that media coverage often ignores victims, focusing instead on perpetrators. Without reforms at the federal level, he warned, meaningful gun control is unlikely.

Turning to politics, Andrew reflected on his 2013 mayoral campaign and criticized the recent Minneapolis DFL convention, which he described as unusually corrupt and damaging to the party’s credibility. While both caucuses and primaries have flaws, he agreed that primaries at least allow more people to participate, even if they favor well-financed candidates. He stressed that the party’s rigid factions threaten its ability to govern effectively.

Andrew’s message was clear: Minneapolis needs accountability, coalition-building, and real investment in human services. Without them, the city will keep recycling the same debates on crime, homelessness, and party politics without moving closer to solutions.