2025 — A Preview of 2026

When First Assistant U.S. Attorney Joe Thompson talks about being understaffed, given the level of fraud his office is uncovering, we believe him. As we write this, it’s being reported that Rep. James Comer, the Republican chair of the U.S. House Oversight Committee, is expanding his investigation into Minnesota’s social services programs.

For most people outside the legislative process, which is to say, most of us, it’s tough to understand how bills are formed, passed, and ultimately held accountable. Tracing the history of just one program can take weeks of research. That reality helps explain why gathering the evidence needed to prosecute fraud has overwhelmed available investigators.

Recuperative care centers are now one of fourteen areas receiving elevated scrutiny.

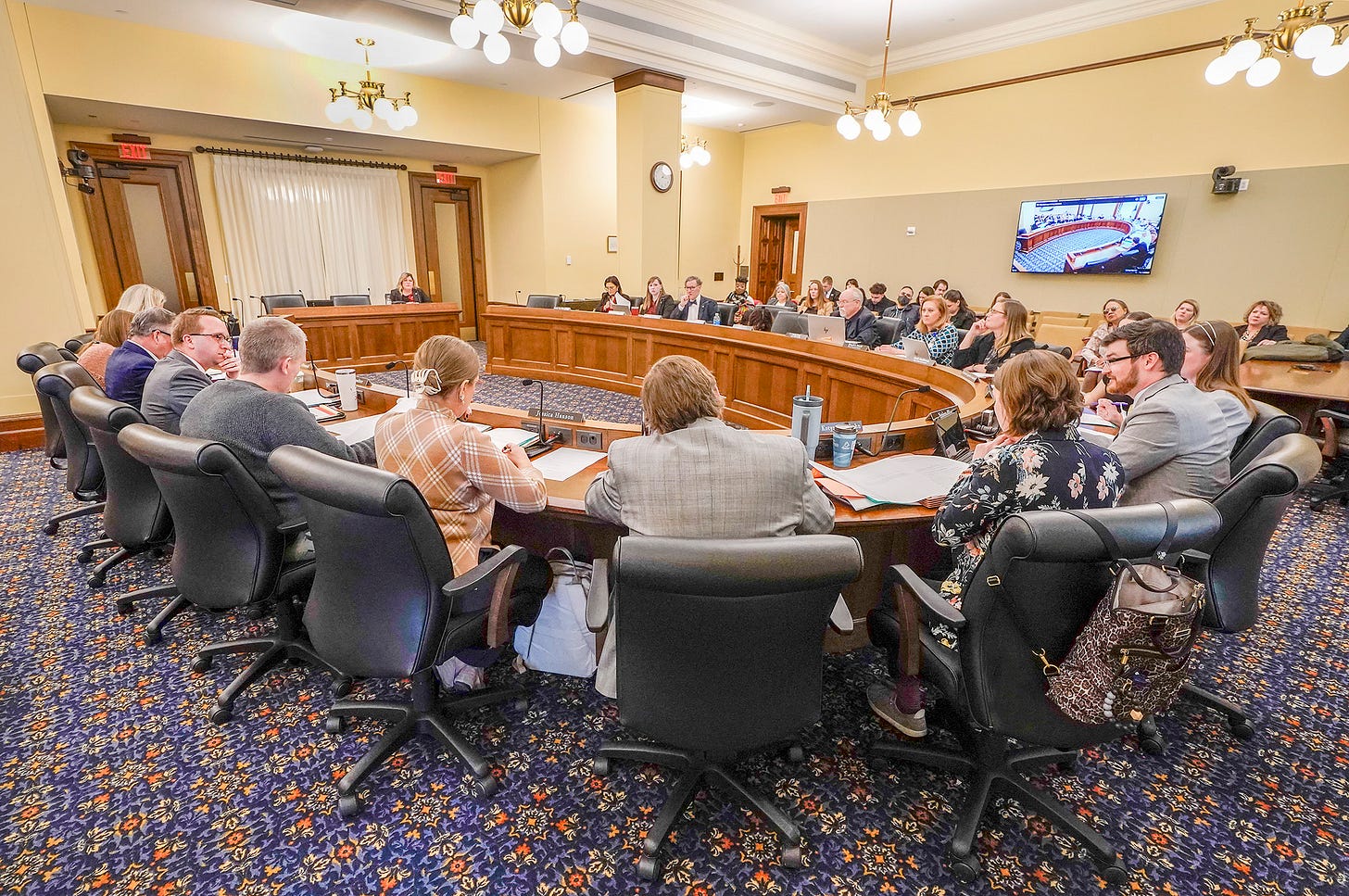

The Medicaid-reimbursable recuperative care program appears to have moved through the House Human Services Finance and Policy Committee in February 2021. We first raised concerns about this program years later, when a facility came before the Minneapolis Planning Commission seeking approval at 918 Lake Street. By that point, the program itself had already been authorized at the state level.

The Planning Commission recommended approval, and the City Council followed suit. It was decided that determining whether the facility was being used as a front for fraud was ultimately the state’s responsibility.

The Committee Will Pass Your Bill Now

Anyone can look up the committee members who voted to advance the legislation establishing these facilities. Among them were Rep. Mohamud Noor (60B) and Rep. Kristin Robbins (37A). Robbins is now the Republican chair of the Fraud Prevention and State Agency Oversight Policy Committee and a leading critic of Gov. Tim Walz, as well as a declared candidate for governor herself.

What stands out is not who voted for the bill, but what the bill failed to include. It contained no clear provider qualification standards and no meaningful requirements for auditing or ongoing oversight. Those omissions alone help explain why so many programs approved in good faith later become vulnerable to abuse.

Whether this reflects initial neglect, misplaced trust, or simple legislative overload, many state lawmakers and elected officials bear some responsibility for the wave of fraud investigations now underway.

By the time these programs reach committee hearings their trajectory often seems predetermined. Well-organized interest groups lobby aggressively for passage, testifying to the promise of new programs and the urgency of action. Once a bill clears committee, scrutiny tends to fade. After final passage, oversight frequently disappears altogether.

Cities and counties are now discovering the consequences. The state has a long-standing habit of authorizing new programs and mandates that local governments are then expected to administer, regardless of whether they supported them or whether the funding is sufficient to do the job responsibly.

Omnigigantica

Each year, our state legislature passes massive omnibus bills—enormous clusters of policy that, to the layperson, are about as decipherable as a Rubik’s Cube. This process makes a mockery of Minnesota’s Single Subject Clause, which requires that all provisions in a bill relate to one general topic.

Unless a journalist is especially motivated to dig into these bills, they often pass with little public scrutiny. And even when someone does take the time, the response is predictable: the reporter’s motives are questioned, they’re lumped into one political camp or another, and the work is consumed almost exclusively by readers who already agree with its conclusions.

This is the media culture we’ve allowed to take hold. It is fueled by outrage, and in that environment, facts have become nearly as malleable as fiction.

2026 Will Not Be “Normal”

We’re going to keep pursuing this story even though it isn’t an easy one to tell. It’s layered and complex, and like most people, we’re naturally drawn to stories with clear villains. What we see instead is a chain of decisions, incentives, and omissions that have allowed Minnesota’s benefits system to be exploited.

At the same time, there is no shortage of dubious voices eager to use this mess to spread misinformation and rumors. The result is an information environment so noisy that even engaged readers struggle to tell which stories are worth their attention and which exist solely to generate outrage.

For now, we’re going to step back for a few days, bake cookies, spend time with people we care about, and focus on what brings us joy. The angst will still be there waiting for us in 2026. And if there’s one thing we’re confident about, it’s that next year is likely to bring as much, if not more, turbulence than 2025 did.

We plan to return the first week of January. At that point, Hennepin County Attorney candidates Francis Shen and Hao Nguyen will be sharing their proposed agendas with us. We’ve also invited Tim Walz and Peggy Flanagan to join the conversation, but they’re still considering it.

This is also a terrific time to become a paid subscriber. Your support helps sustain our work into the coming year. It’s increasingly clear that we’re going to need more people willing to write, question, and think seriously about how we fix what has gone badly wrong in this state.