At an October 6 Ward 9 forum hosted by the League of Women Voters, Council Member Jason Chavez called it “unfair” that supporters of the Roof Depot urban farm and community center continue to be denied what they want. Two days earlier, the Climate Justice Committee had marched through Mayor Frey’s neighborhood, urging him to give the East Phillips Neighborhood Institute (EPNI) what they consider a fair deal on the long-contested Roof Depot site.

A Deal Deferred

For years, the fate of the site has hung in limbo. The state legislature twice failed to approve the $5.7 million that would have allowed EPNI to buy the property for $11.4 million — the price previously agreed upon with the city. The most recent offer, $10.2 million, remains uncertain. According to the city, nearly half that amount—$4.5 million—is restricted and cannot legally be used for the purchase.

The site’s history adds another layer of complexity. Originally acquired by the city to ensure clean, reliable drinking water for Minneapolis residents, the project has already cost $19.1 million in purchase and holding costs. With that investment sunk, city officials now plan to recoup losses by opening the site to competitive bids rather than granting a discounted sale to EPNI.

Community vs. City Hall

Chavez and EPNI’s backers argue that the city should honor the spirit of the deal and support a project designed to bring jobs, food, and opportunity to one of Minneapolis’s most environmentally burdened neighborhoods. City leaders, meanwhile, say they must balance those goals with fiscal responsibility and the broader obligation to maintain critical infrastructure.

In this clash, both sides point to fairness — but they mean very different things by it. For EPNI and its allies, fairness means keeping a long-promised community vision alive. For the city, it means protecting taxpayers from yet another costly reversal. Somewhere between those definitions lies the missing majority — the broader consensus needed to finally move Minneapolis forward.

The Main Issue

Financing has long been a problem for the Roof Depot urban farm project — but an even greater obstacle may be public support. Most residents remain unaware of the proposal, and for good reason: it’s been sustained largely by a small, dedicated circle of advocates over the past decade. Among them is Dean Dovolis, chair of the East Phillips Neighborhood Institute (EPNI) and principal of DJR Architecture, whose firm has received much of the project’s planning and development funding.

At its core, the urban farm is an ambitious experiment — one that could offer local benefits but would require continuous state and city subsidies to operate. That ongoing cost may help explain why the legislature has shown little urgency to allocate the necessary funds.

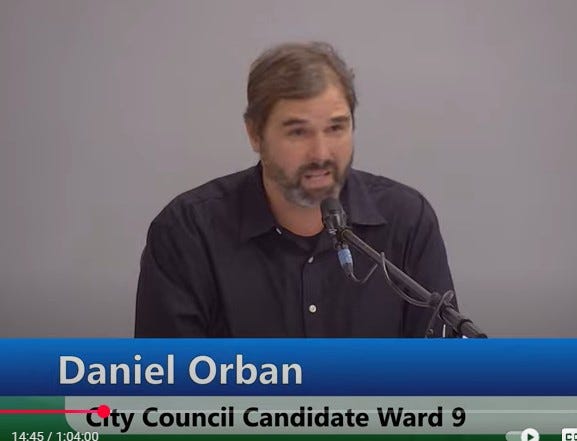

The debate has also become a reflection of differing leadership styles. Council Member Jason Chavez has championed the project as a matter of environmental and social justice, while challenger Dan Orban has emphasized compromise and representing all ward residents. Their contrast highlights a broader question facing the city: how do we balance visionary projects with practical outcomes?

If the goal of the city government is to help the greatest number of residents, other uses for those dollars deserve consideration. For instance, state or city support for families receiving Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits could immediately improve food security for thousands. With federal SNAP funding reduced by $120 billion over ten years in the “One Big Beautiful Bill Act,” local action could make a measurable difference — far more than the urban farm likely could.

The aspirations behind the project — addressing environmental harm and economic inequity — are commendable. But as federal support declines and budgets tighten, Minneapolis must ask a harder question: how can we do the most good with the limited resources we have?

Like the Rise Up Center on Hennepin, the urban farm highlights a broader tension within city policy — between idealism and sustainability. The supporters of such projects are often passionate, well-organized, and skilled at amplifying their message online. To city officials, that visibility can create the impression that these groups represent the will of a much larger public than they actually do.

Because voter turnout remains low in many wards, candidates who align with the most vocal advocates can still secure enough votes to win. Meanwhile, many residents — busy with their families, jobs, and everyday concerns — are left surprised when their elected representative seems out of step with the majority’s priorities.

The solution isn’t to silence activism but to broaden participation. Minneapolis works best when more people show up, speak up, and vote.

And Now, the Overreaction

We expect some readers will take issue with this perspective — and that’s fine. Minneapolis thrives on debate. What’s discouraging, though, is how quickly disagreement turns into denunciation. Too often, those who see themselves as defenders of justice spend more time policing language and motives than building coalitions or solving problems.

What the city needs now are leaders who can balance competing priorities — who listen carefully, weigh evidence over ideology, and make decisions guided by results rather than rhetoric. There are already plenty of passionate advocates willing to fight symbolic battles. What Ward 9 residents told us they want, in plain terms, is a functioning 3rd Precinct. The applause that followed Dan Orban’s mention of reopening it said as much, even if it caught the moderator off guard.

City government isn’t meant to mirror the national culture wars. Its purpose is simpler and more tangible: keeping the streets safe and clean, partnering with the county to reduce drug use and encampments, and helping young people find better options than car theft or truancy.

This November, Minneapolis has a chance to reward leadership that focuses on the practical over the performative. For Minneapolis to truly recover from the past five years, it needs public servants who value results over rhetoric — leaders focused on delivering for all residents, not just the loudest voices.